What I know now that I wish I knew then…

Growing up in a home daycare. Written by Katie Bertrand, RECE

I grew up in a small town, and from when I was little until my early adolescence, our house was “the house”—the house that everyone in the neighborhood was a part of.

My mom ran a home-based daycare, and when you live in a small town and your mom runs a daycare there is a pretty good chance everyone knows you, and at one time or another every neighborhood child has called your place a second home for 9 hours a day. We always had a house full of little ones, some for a long time, some that just came for a while, some that are still a part of our life, and so many that left lasting memories.

When you are a child living in the home of a home daycare you become accustomed to a life where nothing is only yours. Everything is communal, you share toys, you share living space, you share pets, and even your bedrooms are transformed into nap rooms in the afternoon. There were times when I hated it, and wished I could just have my own space. I’m sure on many occasions I uttered the words “I will never run a home daycare when I grow up”.

Well, I grew up and it was time to decide on where to go after high school. I decided to get my diploma in Early Childhood Education with the plan to continue to teachers’ college. Still with the mindset that “I will never run a home daycare as my mom did”. Time went on and life happened and after many years of working in a licensed child care centre, I found myself at a turning point. I had my first child…how could I justify putting them in child care when that was my life? So, it happened, the thing I said I would never do—I opened a home daycare.

I was lucky and found some great families right off the start and slowly, as the years progressed, my business grew. Along came my second child and this career choice made even more sense. Being a RECE, I ran my daycare business with a play-based learning philosophy and a heavy emphasis on outdoor time. Something I learned from watching my mom run her business, you know…that business I said I would never do when I grew up.

Over the years many children have come through my doors and so many times I have thought back to my childhood and all the children that came and went. Every job has trade-offs, but running a home daycare has unique ones. I tried to be aware of the fact that my children and husband were sharing their home with five other families, and sometimes privacy was at a minimum. When they came down in the morning for breakfast there was a high possibility other children were sitting at the table already eating, and one of my children is not a morning person, so the little ones were not always greeted with a happy face and that was ok, because this was their home and their space, and they didn’t always need to be “on”.

I am pretty sure I’ve heard my children utter the words “I will never run a daycare like my mom”, but now that time has passed and my children are growing into young adults, I know now what I wish I realized when I was their age, that growing up in a home daycare was a wonderful childhood. The lifelong skills I learned have followed me throughout my whole life.

My two children and two dogs learned so much as we welcomed new little ones into our home who had never been away from their parents. They learned to be patient and empathetic as mom doesn’t have 5 arms. They learned how to share and communicate, from a very young age sharing mom was part of the job, and that was not always easy. They also learned that mom was always there for drop off and pick up from school, and there were always five smiling faces so excited to see them walk in the door. They learned there were many other moms and dads in their world now who were always excited to hear about all their accomplishments at morning drop-off. What I hope they eventually learn, like I did, is that being a home daycare provider is one of the most important and rewarding jobs and when someone chooses this profession, they are choosing to have a lasting impact on so many little lives that shape our future.

Fall Fun With Your Toddlers & Preschoolers

Written by RaDeana Montgomery, RAM Media

Autumn is a wonderful and magical time of the year, especially for children. The vibrant colours of the leaves, the crisp air, and the abundance of pumpkins make it an excellent season for outdoor activities with toddlers and preschoolers.

Here are ten fun and educational ideas that, as a child care provider, you can incorporate into your planning.

- Leaf Scavenger Hunt: Take your children on a nature walk and have them collect different types of leaves; you can teach them about the various shapes and colours of the leaves, and for more leaf fun, bring some back with you and let the children colour or put faces on the leaves, making great art pieces for parents to hang and enjoy.

- Nature Art: Aside from collecting leaves on your nature walk, look for acorns and pinecones, collect them, and use them to create nature-inspired art.

- Fall Picnic: This one is simple to do. Organize a fall-themed picnic in your backyard or park. Bring autumn snacks like apple slices or warm cider for the children to enjoy.

- Leaf Pile: This activity is fun for all ages. Rake the leaves into a big pile and let the children enjoy jumping and playing. Jumping in leaves is a classic activity everyone will enjoy with a laugh or two.

- Storytime in Nature: Find a cozy space outside and read a fall-themed children’s book. Encourage discussions about the changing seasons and the animals that are getting ready to prepare for the winter. Watch for squirrels that are gathering nuts for the winter. The book Sky Tree: Seeing Science Through Art, by Thomas Locker, is lovely.

- Scarecrow Making: This can be a lot of fun. Work together to create a friendly scarecrow using old clothing. Have the children each bring a piece of clothing, stuff with leaves or hay, and use a pumpkin for the head. Or be creative and use other elements that you might have at home. This activity is fun for teaching children about recycling and about the purpose of a scarecrow.

- Harvest Sensory Play: Set up sensory bins with materials like dried corn, colourful leaves, acorns, and gourds. Sensory play allows children to explore all different textures, shapes, and sizes.

- Fall Scavenger Hunt: Make a scavenger hunt list or use pre-made printable graphics to show the children what you will be looking for. Take a walk in your backyard or local park and see how many items on the list you and the children can find together. Take pictures of everything and create a picture book of the adventure together.

- Handprint Leaf Picture: This will be one of those extraordinary works of art parents will keep forever. It can be messy, so it is best to do it outside, but the memories it creates will make up for that. Use a canvas or large piece of paper. Paint a trunk, then let the children go to town making leaves with their hands and finger prints. When the little artists are done, you will have a beautiful work of art.

- Pumpkin Decorating: Have a pumpkin decorating session where children can paint, draw on, or stick decorations to their pumpkins.

Remember always to prioritize safety and supervision during outdoor activities. These experiences let children appreciate the beauty of fall and offer opportunities for hands-on learning and development. Autumn is one of the best seasons for children to explore and engage with nature.

Empowering Growth: Growth Mindset for Parents and Caregivers

Written by Krystal Kirkwood, RECE

As parents and caregivers, we have the incredible opportunity to shape the mindset of our children. But it is equally important to develop a growth mindset within ourselves. By embracing a growth mindset, we can model resilience, inspire lifelong learning, and create a positive environment for our children. In this blog post, we will explore the differences between a growth mindset and a fixed mindset and share simple ways for parents and caregivers to foster a growth mindset within themselves.

A Growth Mindset will embrace challenges and personal development. A growth mindset means believing that our abilities and intelligence can be developed through effort and learning. It is about seeing challenges as opportunities for growth, rather than obstacles. With a growth mindset, we understand that our skills and capabilities can improve with dedication and practice.

A fixed mindset is when we believe that our abilities and intelligence are fixed traits that cannot significantly change. People with a fixed mindset tend to stay within their comfort zones, avoid challenges, and fear failure. They may believe that their skills are predetermined and limited.

Developing a Growth Mindset Within Ourselves as Parents and Caregivers:

- Embrace New Challenges: Step outside of your comfort zone and embrace new challenges. Take on tasks or learn new skills that you have always wanted to explore. By doing so, you model the courage to grow and inspire your children to do the same.

- Learn from Mistakes: Embrace the idea that mistakes are valuable learning experiences. Instead of dwelling on failures, focus on the lessons learned and the improvements you can make. Show your children that mistakes are not setbacks, but steppingstones to success.

- Cultivate a Love for Learning: Set aside time for your personal growth and learning. Pursue hobbies, read books, take online courses, or engage in activities that stimulate your mind. Share your newfound knowledge and excitement with your children, inspiring their curiosity and love for learning.

- Practice Positive Self-Talk: Be aware of your own self-talk and challenge any negative or limiting beliefs. Replace self-doubt with self-encouragement and affirmations. Cultivate a mindset that believes in your own capacity to learn and grow.

- Set Realistic Goals: Set goals for yourself and break them down into manageable steps. Celebrate your progress along the way, acknowledging the effort you put in. By demonstrating goal setting and perseverance, you teach your children the value of continuous improvement.

- Seek Support and Collaboration: Surround yourself with like-minded individuals who also embrace a growth mindset. Engage in discussions, seek advice, and collaborate with others who share your desire for personal growth. Create a support system that fosters growth and resilience.

When we practice the skills of growth mindset as parents and caregivers, we can become powerful role models for our children. As you foster a growth mindset within yourself, you will create an environment that encourages your children to embrace challenges, persevere through obstacles, and unlock endless possibilities. Join us on this journey of growth together and inspire children to believe in their ability to learn and achieve great things.

Empowering Growth: Nurturing a Growth Mindset in Children

Written by Krystal Kirkwood, RECE

As parents and caregivers, we want to see our children thrive and reach their full potential. One important factor in their success is their mindset. In this blog post, we’ll explore the differences between a growth mindset and a fixed mindset and share simple ways to nurture a growth mindset in the children you care for.

Understanding Growth Mindset:

With a growth mindset we can embrace challenges and learn from mistakes. A growth mindset is when children believe they can improve their abilities through practice and effort. They see challenges as opportunities to grow and learn. They understand that that it’s ok to make mistakes and can learn from them.

Exploring Fixed Mindset:

With a fixed mindset we are stuck in limitations and fear of failure. A fixed mindset is when children believe their abilities are fixed traits. They may avoid challenges because they fear failure and believe that making mistakes means they’re not smart or talented enough.

Fostering a Growth Mindset in Children:

- Encouraging Effort and Progress: Focus on praising the child’s efforts and the progress they make, rather than their achievements. E.g., “Wow that was really hard for you, but you kept trying, you did it!” This will teach them that hard work and perseverance are more important than success.

- Teach the power of “yet”: When your child says, “I can’t do that!” add the word “yet” to the end. This simple word encourages them to believe in their ability to learn.

- Emphasize the learning process: Help the children in your care to understand that learning is a journey. Encourage curiosity, exploration, and a love for learning new things. Show them that mistakes are opportunities to learn and improve.

- Set realistic goals: Help the children set achievable goals that require effort and progress. Break bigger goals into smaller steps and celebrate their accomplishments. E.g., The child who is learning to zip up their zipper independently. You can start the zipper for them, but don’t zip it up all the way, allow the child to do this. Then say, “YOU DID IT!” with excitement. This will build their confidence and motivation.

- Be a role model: Children learn by observing their parents and caregivers. Model a growth mindset by sharing stories of your own challenges and how you overcame them. Show them that setbacks are temporary and how “sticking with it” leads to growth.

- Provide support an encouragement: offer kind guidance and support when your child faces difficulties. Encourage them to try different strategies and provide positive reinforcements for their efforts, regardless of the outcome.

By nurturing a growth mindset in children, we empower them to approach challenges with resilience, and foster a love for lifelong learning. Encourage effort, teach the power of “yet”, emphasize the learning process, set realistic goals, be a role model, and provide support. With your positive guidance and belief in their ability to learn, the children in your care will develop a mindset that opens doors to endless possibilities.

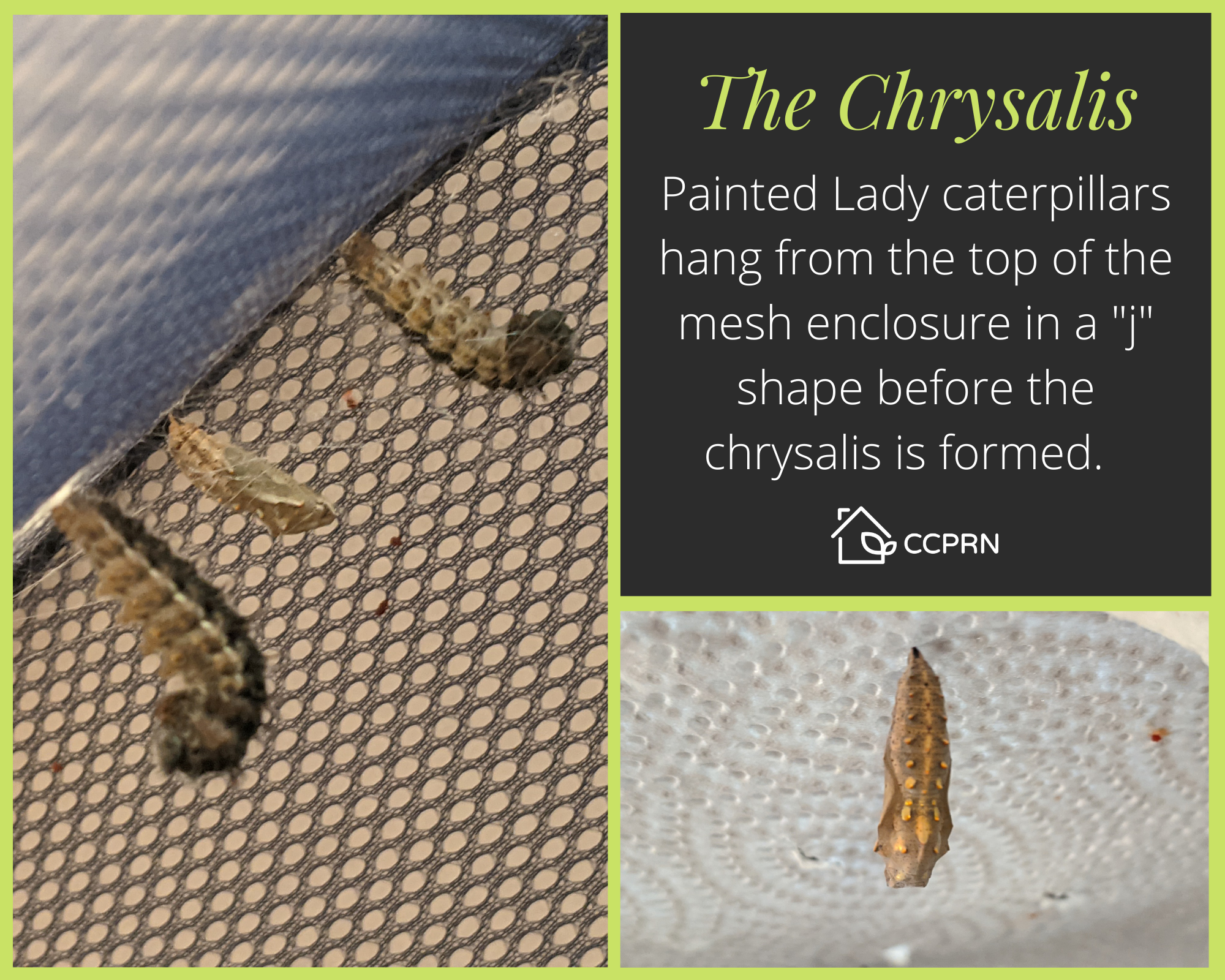

Caring for Caterpillars

Written by Julie Bisnath, BSW RSW

Perfect for a home or child care environment, welcoming live caterpillars is easy and engaging. The caterpillars arrive in their own individual cups with their food included. You provide the habitat, which can be as simple as a jar or small mesh laundry hamper. Once the butterflies emerge, they spend a couple of days drying their wings, providing lots of time for up-close observation. On a nice day, release the butterflies in your yard or garden.

This wonderful experience offers many opportunities to:

- invite children to explore and enjoy caterpillars and butterflies up close

- inspire curiosity and a love for nature

- help children make meaningful connections to the environment & the world around them

- encourage children to wonder and develop their own theories

- examine nature from a scientific perspective

- foster a love for and gentleness toward all living things

Ready to get started?

- Order your Painted Lady caterpillars online at ccprn.com/shop

- 5/$35

- Pick-up your caterpillars in early June 2025 (exact date to be confirmed closer to June, pick-up will be in the evening) in Orleans, Ottawa Central, Barrhaven, or Stittsville.

- Observe and enjoy watching them grow. After 1-2 weeks they will transform into the chrysalis and in 8-10 days will emerge as butterflies.

- Observe and enjoy the butterflies for a few days and then release them outside.

Caring for your caterpillars and butterflies:

5 caterpillars will come in one small container with a cover. In the container with the caterpillars, there is a spoonful of artificial diet (soya flour based).

Leave the container on a shelf away from direct sunlight (and away from pets!) and at room temperature. You can open the cup for a closer look and even very gently hold the caterpillar. The caterpillars grow quickly! Be sure to spend some time enjoying this stage.

The images below feature 1 caterpillar per cup. The 2025 order will be 5 caterpillars per cup.

The caterpillars will manage alone and when they are finished feeding, they will push away the frass (caterpillar poop!), hang upside down and transform into a chrysalis or pupa without your help.

When this happens do not disturb the pupa for 72 hours until it has dried, hardened, and is solid.

Once the pupa is dried and solid, pull the paper towel and chrysalis from the container and pin it into a small flight cage (small mesh hamper—good if you have several caterpillars), about three inches from the bottom. It must be high enough for the butterfly to spread its wings completely and dry them when it emerges. If the pupa is pinned too high in the cage, the butterfly could fall and hurt itself. If the emerging butterfly falls from its chrysalis, it must be able to crawl up again in a hurry to dry its wing, so your flight cage must have a rough wall for it to crawl up. Slippery plastic or glass containers will not do the trick unless you add a wooden branch.

Alternatively, you can place the paper towel and chrysalis on the bottom of a jar or bug container. Include a stick to allow the butterfly to hang from once it emerges. Be sure to cover your jar with some sort of breathable material (mesh, a piece of screen, etc.).

Once the chrysalis becomes translucent, the butterfly will soon emerge. The paper towel and chrysalis shown above were placed at the bottom of the container. When the butterfly emerges it can climb onto the stick and up the branch (not shown) where it will dry its wings.

In all, the pupa stage will last eight to ten days. Once the butterflies emerge, they will spend some time (could be a day or two) drying their wings. Place a slice or two of orange at the bottom of the enclosure for the butterflies to drink. Release the butterflies a day or two later into your yard or garden.

Another option:

When the caterpillars are quite large, open the lids of the tiny cups and place them into a larger jar or enclosure (make sure that the lid is breathable yet secure!). Provide sticks for climbing and when the caterpillars are done eating, they will climb to the top and hang directly from the mesh, or from a larger sheet of paper towel.

One caterpillar in a small jar or container is fine if you plan to release it as soon as the butterfly emerges. If you have several caterpillars and/or want to observe them for a couple of days as butterflies, then a larger enclosure is better. This could be a mesh laundry hamper, a small aquarium/terrarium, or even a clear plastic bin with a screen or mesh lid. Include sticks, rocks, and greenery so that the butterflies can climb up and spread its wings once emerged. Information on host plants for Painted Lady butterflies is abundant. Search it up online and you might learn that you already have the perfect host plant growing in your garden!

Several butterflies in a large mesh enclosure, soon to be released outside:

Release the butterflies on a warm day in your yard or at the park:

When a Pet Dies–Supporting Children in Their Grief

Adapted from "Grief and Loss: A Resource Guide for Parents and Home Child Care Providers"

Often, one of the first and most common grief experiences for young children is the death of a pet–whether a beloved family pet or a special pet at a caregiver’s home.

Just as with the death of a person, and depending on their age and development, every child will react differently to the death of a pet. Be patient and reassuring as you talk to children in a way that is age-appropriate and sensitive.

You can support children by:

- Keeping to the facts (use your discretion regarding the details) and using words that are direct and honest but not scary. Use simple language and truthful explanations: “He died.”, “She was very sick/old and her body stopped working.”, “They’re dead. They can’t eat or breath or walk anymore.”, “She died. Died means she’s not coming back. We won’t see her again.”, “We can still think about him and remember the special times we had together.”. Avoid euphemisms such as “put to sleep”, “gone to a better place”, “lost” or “crossed the bridge”. These terms can be confusing and lead to misunderstanding.

- Answering their questions as best you can–if you don’t know an answer, just say so.

- Encouraging them to share their feelings, whether sad, mad, scared, etc.

- Sharing your sadness and/or your own personal pet loss story.

- Modeling and building empathy. Express your own feelings : “I’m sad too. I’ll miss feeding Finn and watching him swim around” and give children the opportunity to express theirs. Help them to build empathy when a friend is grieving: “She’s sad. Her dog died and she misses him. What can we do or say to tell her that we care?”.

- “I wish…, I miss…, and I remember…” are good starting off prompts. Some children will join in and want to share while others might prefer to listen as you share your thoughts and feelings.

- Wondering together. Some questions have no answers. It’s ok to say that you don’t know the answer but that you’re glad that you can wonder about it together.

- Offering comfort–be close and be present. Respond with care and kindness and reassure children that they are safe, cared for, and loved.

- Reading together–picture books can help children to process their feelings.

- Encouraging children to play. This is how they work out difficult situations and make meaning of events they don’t quite understand.

- Celebrating the pet’s life with a special gesture—Invite the children to take a favourite walk, draw a portrait of the pet, plant a flower or tree, paint a memorial rock, blow a wish, sing a song, etc.

Children are naturally curious about life and death. Turn everyday moments into an opportunity to talk about the life cycle. Observing plants and insects often provides a natural segue to talking about death. Understanding the inevitability and irreversibility of death takes time. As children grow and develop, they begin to process and accept these concepts. Introducing the language and simple facts can help to prepare children for the death of a pet down the road.

Know that each child will process their grief in their own way and in their own time. Being present, giving children the time and space to work through their emotions, wondering together about the hard questions, and bearing witness to their pain will all help to validate their grief.

Interested in learning more? Check out our e-book Grief and Loss: A Resource Guide for Parents & Home Child Care Providers. Topics include:

- How do children grieve? Common reactions and ways to offer support

- A note about separation and divorce

- Talking about death

- Ways to honour and celebrate life

- Book suggestions and reading lists

- Recommended resources

You can download a free copy of the guide on the Resources section of our website.

We All Worry

Adapted from "Anxiety: A Resource Guide for Home Child Care"

We all worry—some more than others. The same is true for children. It is natural and normal to worry and have fears. In fact, it is very common for young children to express a wide range of worries. The world is new, and their frame of reference is small. Worry and fear are different forms of anxiety and are a normal part of development.

The brain’s alarm system alerts us to threat and keeps us safe—that little voice, those gut feelings, the spontaneous physiological symptoms—they all have a purpose, and thankfully so. Plus, we’re all familiar with fight, flight, or freeze—the most common reactions when faced with danger. This is your brain, doing its job to keep you safe. Letting you know that something’s not right. For some people though, their internal alarm system is naturally more sensitive and therefor more easily activated. They worry more.

Preparedness and prudence help to keep our worries in check. Preparing for a test, new job, or presentation will often lessen the worry and help to keep us calm. With increased preparedness, the level of threat decreases. Similarly, being prudent in a potentially dangerous situation (i.e., wearing a seatbelt or bike helmet) can also help to minimize the risk of danger and keep us safe.

Because young children can’t judge what is dangerous, they don’t prepare for danger and aren’t prudent enough to be careful and avoid it. It’s the adult’s job to keep them safe. Through our relationship with a child, we can help to calm their alarm system by being present, acknowledging their worries, and helping them to understand the likelihood and/or severity of the threat.

When children are young, and their experiences are all new, their frame of reference is very small. Many experiences present as a potential threat resulting in some children having lots of worries—especially those with more sensitive internal alarm systems.

For example: An infant who loses sight of their parent truly doesn’t know where that parent went or if they ‘ll be back—Where are you? Who will take care of me? Who will keep me safe? They cry and learn that although we might be out of sight, we are close by and will always respond to their needs. As they grow and experience more frequent and prolonged types of separation (nighttime, being cared for by Grandma, child care, etc.), they learn that the parent always returns which builds trust in the relationship. Their worries are calmed by that knowledge and by the predictability of the experience—the parent’ s consistent return. Eventually, this worry dissipates, and the child is comfortable going to school, to a friend’ s house, and before you know it—moving out on their own. Their frame of reference for “being apart” is large and they are able to stay connected without having to have the parent within sight.

Understanding the brain’s alarm system and a child’s limited frame of reference helps to explain why they worry. When we understand why children worry, we are better able to support them in their ability to handle their own fears and worries.

Interested in learning more about common childhood fears and how exactly you can help? Take a look at our free e-book Anxiety: A Resource Guide for Home Child Care. Available as a free download under the Resources section of our website.

Transitioning to Child Care

Written by Julie Bisnath, BSW RSW

Home child care providers are one of the most influential people in a child’s early life—helping to shape the developing brain and laying a strong foundation for future learning and growth. A quality home child care environment features a caregiver who is committed to the well-being and safety of the children in their care. This commitment begins during the transition phase as the caregiver works to establish a secure attachment and foster a deep sense of belonging for each child.

A secure attachment—the component of an adult-child relationship relating to the child’s safety and security—develops from a consistent, reliable, responsive, and caring relationship. It is within this secure attachment that young children learn to trust others. It also provides them with a safe place from which to explore and investigate the world. Feeling secure and having a strong sense of belonging allow children the freedom to learn and grow.

One of the most fundamental and intimate human needs is the need for connection and belonging—the feelings and experiences of being valued and of forming meaningful relationships with others. Ontario’s pedagogical document How Does Learning Happen? describes belonging as a core foundation of the framework.

“When children are strongly connected to their caregivers, they feel safe and have the confidence to play, explore, and learn about the world around them. Enabling children to develop a sense of belonging as part of a group is also a key contributor to their lifelong well-being. A sense of belonging is supported when each child’s unique spirit, individuality, and presence are valued.” How Does Learning Happen? Ontario’s Pedagogy for the Early Years, page 24

Home child care environments allow children to grow and learn within the comfort and structure of a family setting. Just as with any family, connection and relationship between the members of a home child care family are essential. A strong foundation of trust, open communication, mutual respect, and kindness between a parent and provider will allow the child to flourish.

All children are different and each child will adjust to child care in their own time and way. Factors including the child’s age, communication skills, and comfort with being left in the care of others, all contribute to how a child might react when starting child care. Here are a few general things to expect:

- A range of emotions that might include excitement, joy, apprehension, sadness, and/or worry.

- A possible change in behaviour and/or eating/sleeping/toileting habits.

- Days that are easy and days that are hard.

We know that starting child care can be hard. With this in mind, we’ve set out to offer a range of practical suggestions and online resources for both parents and providers. Tools and tips to help ease the transition, establish a sense of belonging, and pave the way for a successful child care partnership.

“Transitioning to Child Care: A Guide for Parents and Home Child Care Providers” includes information on all of the following topics:

- Transitioning during COVID-19

- Easing the transition–what parents can do and what providers can do

- Napping and Breastfeeding during the transition period

- Saying goodbye and cherishing connection

- Transition schedules

- Picture book suggestions

- Transition rituals

- Using a visual schedule

- Creating a Family Wall

- Extreme separation and other anxiety disorders

You can read the full guide here: https://ccprn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Transitioning-to-Child-Care-Final-Sept-2021.pdf

For the Love of Sharing

Written by Julie Bisnath, BSW RSW

Sharing—such a hard concept for young children. And teenagers. And let’s face it, many adults too. It’s one of those words that we assume has one “shared definition” but really it doesn’t. It in fact has several definitions and depending on the situation can be a rather confusing word.

Share your toys. Share your cookie. Share the couch.

There’s a lot going on with that one word. It’s no wonder that it can be confusing for children when we use the same word to mean different things.

When we say “share your toys”, what we usually mean is take turns or lend your toy for a little while. “Share your cookie” is completely different. That half will disappear, never to return! “Share the couch”, is different again. We’re asking to share the space, make room, or move over.

It helps young children to learn and understand the different meanings if we use more specific language detailing what it is that we are asking.

Semantics aside, sharing is a pretty loaded word, rife with pressure and judgement. Why do I have to share? What if I don’t want to share? What if I don’t want to share with you in particular? If I don’t share am I a bad person? Am I selfish? How do I decide? How do I know?

Why do we expect children to share when we as adults don’t always? Do you always share your food? Do you share items that are valuable to you? Would you trust just anyone to take care of your special things/pets/children? Would you still share something with someone who has broken your trust (someone who never returns things or has returned something damaged)? What about something that you are using—your car? Your phone? Would you just give it up because someone else asked to use it?

I’m not sure that there are any easy answers. What’s right for me is right for me and what’s right for you is what’s right for you. The item in question, the people involved, and the context of the situation are all relevant factors. There are no right or wrong answers. What I do know, is that for sharing to be meaningful, the motivation for it needs to come from within. I love Raffi’s song for highlighting this concept “It’s mine but you can have some, with you I’d like to share it, cause if I share it with you, you’ll have some too!” Sharing because I want to feels good and is meaningful to me.

When we tell children “you need to share”, or “you’ve had the doll long enough”, or “Jo’s going to have a turn now” we are imposing the act of sharing and teaching them that sharing feels bad. Instead of insisting on sharing we can teach our children to consider the request (or better still notice and observe: “I see that Jo has been waiting and watching you for a long time now…”) and make a decision. If they decide to share, great. If not, that’s ok too. Teach them to kindly and assertively let the other child know that they are not done or are not ready/willing to share. Help the other child to wait and be patient, and to accept the decision. Distraction and redirection often work well. In her post “It’s OK Not to Share”, author Heather Shumaker gives great examples of words to use:

Positive assertiveness

– You can play with it until you’re all done.

– Are you finished with your turn? Max says he’s not done yet.

– Did you like it when he grabbed your truck? Tell him to stop!

– Say: “I’m not done. You can have it when I’m done.”

– She can have a turn. When she’s all done, you can have a turn.

– I see Bella still has the pony. She’s still using it.

– You’ll have to wait. I can’t let you take it out of her hands.

Waiting and awareness of others

– Oh, it’s so hard to wait!

– You’re so mad. You really want to play with the pony right now!

– You can be mad, but I can’t let you take the toy.

– Will you tell Max when you’re all done?

– I see you’re not using the truck any more. Go find Ben. Remember, he’s waiting for a turn.

Sharing (space or toys) at home (or at child care) can be encouraged but does not necessarily need to be enforced or policed. Longer turns can be allowed and the children can practice using some of the language noted above. The more opportunities that they have to practice turn taking the better they will become at expressing themselves and regulating impulse control and emotions.

Sometimes, adults do need to guide the play. In a public space for instance or during a group activity an adult might have to remind the children that the toys and equipment are for everyone. Turn taking might need to be discussed ahead of time: “Today at playgroup, you can have a turn on the slide and so can all of the other children”. Another example might be to talk about sharing toys and turn taking when hosting a playdate. It’s ok if there are certain special toys that your child does not want to share. Put those toys away for safe keeping only to be brought out once the playdate is done. The same is true for taking special toys to child care. On the one hand, if it will be hard to share the special toy then it might be best left in their cubby or backpack. On the other hand, it is also important for children to learn that not everything is for sharing. Discuss it with your child care provider to determine how best to proceed.

To share or not to share–it’s not easy, to say the least, and takes a lot of practice and patience. When we model the language of sharing (positive assertiveness and waiting) we are teaching lifelong skills and increasing resiliency. When we, as adults, feel intrinsically motivated to share with others, our children will witness this kindness and learn from our example. Best of all, when they feel motivated to share, and when they make that decision for themselves, we’ll know that it’s sincere and comes from the heart.

References:

- www.raffinews.com/files/music_arrangements/childrens_favorites/sharing_song.pdf

- www.positiveparentingsolutions.com/parenting/its-ok-not-to-share