Risky Play–Essential for Healthy Child Development

Written by Julie Bisnath, BSW, RSW

Risky play is exactly that—play that involves risk—usually the risk of physical injury. It is exciting and exhilarating and thrilling and, well, risky. It does, however, provide children with much needed opportunities to challenge themselves physically, emotionally, and mentally. Risky play allows children to test the limits of their abilities, develop an awareness of risk, and feel in control of their actions. Plus it’s FUN! How do I know? From observing the shrieks of joy, the belly laughs, the nervous giggles, and the huge smiles that come from feeling confident and capable. Researched and developed by Norwegian professor Ellen Sandseter, risky play encompasses eight categories of risk, as perceived by a child 1.

- Great Heights—climbing, jumping, balancing, etc. with a risk of falling

- High Speed—uncontrolled speed and pace while running, biking, sledding, etc. with a risk of collision or injury

- Dangerous Tools—knife, axe, saw, etc. with a risk of injury

- Dangerous Elements—fire pits, cliffs, open bodies of water, etc. with a risk of falling or injury

- Rough & Tumble—wrestling with other children, roughhousing, fencing with sticks, snow ball fights, etc. with a risk of injury

- Unsupervised play—exploring alone with a risk of getting lost

- Impact—crashing into things for fun with a risk of injury

- Vicarious—the thrill of watching other (often older) children take risks

When provided with the time, space, support, encouragement, and appropriate level of supervision (risky play is not a free-for-all), children can actively pursue and enjoy this type of daring play. Think back to your own childhood and hopefully you’ll find memories of being outdoors, engaged in play fraught with risk and adventure. I grew up in the city, but here’s what I remember best— a farm, a wooded park, a junk yard, a creek’s edge, an open field, and hours of fresh air and fun. I played by myself, with my sister, with friends, and with random children I hadn’t met before or didn’t really know. My mom would be close, but not too close—probably a good yell or two away.

Now I know that times have changed, and most parents prefer to keep a closer eye (myself included!) and I certainly am not advocating for caregivers to be “a yell or two away” but it is good to reflect upon and consider how we (parents and caregivers) might adapt our practices to include more elements of risky play. We know from our own experiences that the benefits far outweigh the potential risks and we have the full support of many leading health and research organizations including the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Toronto’s Sunnybrook Centre for Injury Prevention, and the Canadian Public Health Association—all of whom advocate and promote risky, unstructured play.

In a position statement supported by CHEO, risky play is explained as “giving children the freedom to decide how high to climb, to explore the woods, get dirty, play hide ’n seek, wander in their neighbourhoods, balance, tumble and rough-house, especially outdoors, so they can be active, build confidence, autonomy and resilience, develop skills, solve problems and learn their own limits.”2

Why is risky play important?

Good things happen when children are encouraged and supported in risky play. Driven by curiosity, they naturally want to explore and be adventurous. When children are curious, they explore, ask questions, and make discoveries. In doing so, they learn and grow in all areas of health, development, and well-being. Children engage in pro-social behaviour (communicating, negotiating, co-operating), improve executive functioning abilities (goal setting, attention span and focus, spatial working memory, judgement, planning, etc.), and learn how to keep themselves safe (understanding what feels safe, knowing the limits of their skills and abilities).

“When children experience the uncertainty of challenging or risky play, they can develop emotional reactions, physical capabilities and coping skills that expand their capacity to manage adversity. These skills are important for resilience and good mental health in childhood and into adolescence.”3

Life is full of risks and uncertainty—if we want our children to grow into adolescents and adults who are capable of making good decisions and have sound judgement then we need to give them lots of opportunities to practice and develop these skills. If we as adults constantly decide for them what is safe or unsafe how will they learn for themselves? Risk assessment is a regular and ongoing element of adulthood—we routinely evaluate physical risk, emotional risk, financial risk, sexual risk, etc.—and we each define and measure risk differently. What’s risky for me might not be risky for you. Knowing how to evaluate risk comes from practice. Understanding your body, how it moves, and what feels safe comes from doing. When we teach our youngest children about risk by providing them with appropriate opportunities to practice risk assessment and management skills, we are paving the road for our teenagers who will most certainly be challenged with a risky suggestion or two. Learning and practicing how to assess risk according to your own abilities and comfort levels lends itself to being comfortable with setting limits and boundaries. If children grow up learning to identify and express what feels safe, it will be much easier for them as young adults to say “No, I don’t want to”, or “No, I don’t feel comfortable”, or (and maybe most importantly) just “No”.

“Children rehearse handling risky real-life situations through risky play; and they discover what is safe and what isn’t.”4

How to support risky play:

Risky play is adventurous play—and it can be tailored to children of all ages and abilities and to various levels of risk tolerance.

- Caregivers and parents can work together to decide on how best to incorporate elements of risky play at home and at daycare. Obviously, all existing health and safety regulations should be followed.

- If you are away from home, assess the space and remove hazards (broken equipment, unsafe items—such as needles, broken glass, rusty or sharp metal).

- Use common sense to provide age-appropriate and ability-appropriate time, space, and freedom for children to build skills and figure things out for themselves. Infants busy crawling might enjoy a variety of natural textures (grass, sand, mud, etc.) or low obstacles (small hill, cushions to crawl over, etc.) and obviously require constant supervision. Risky play for a toddler might include balancing on large, low rocks or running freely in a large field. Preschoolers might find it exciting to climb a tree or build with real wood, a hammer, and nails. Older children may well enjoy the freedom to explore greater heights and speeds.

- Do not push children beyond their comfort. Each child will be unique in their willingness and readiness to explore risk and that’s ok. Follow their lead.

- Outdoor play, in natural settings, in a variety of weather conditions, is essential. Think about tall grass, hills, mud, muck, large boulders, trees for climbing, logs for balancing, barns, etc. Natural settings are perfect for mixed age groups because there is always something for every age and ability. Even a large grassy field provides elements of risk.

- When considering your yard, incorporate loose parts and materials—tires, tree stumps, burlap, rocks, logs, bricks, etc.

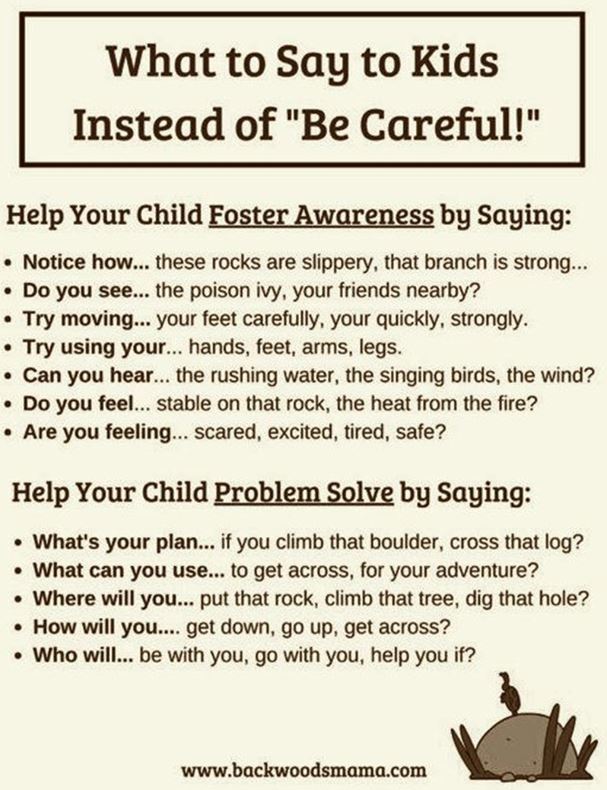

- Provide guidance. Talk about danger. Talk about risk. Ask questions to prompt reflection. “How did that feel?” “What helped you decide?” “How will you…?”

- In the absence of an immediate safety concern, count to 30 before inserting yourself to allow children to assess the situation first and try to problem solve independently. It’s amazing to see the creativity and ingenuity of young children–they truly are capable and competent learners.

- Supervise but… get out of the way! Watch carefully for potential safety concerns but also observe the pure joy and delight that the children are sure to experience.

“Access to active play in nature and outdoors—with its risks—is essential for healthy child development. We recommend increasing children’s opportunities for self-directed play outdoors in all settings—at home, at school, in child care, the community and nature.”5

References:

- http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/outdoor-play/according-experts/outdoor-risky-play

- http://childnature.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/B.-EN-Active-Outdoor-Play-Position-Statement-FINAL-DESIGN.pdf

- https://www.cpha.ca/unstructured-play

- www.schooleducationgateway.eu/en/pub/viewpoints/experts/spaces-for-risky-play.htm

- http://childnature.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/B.-EN-Active-Outdoor-Play-Position-Statement-FINAL-DESIGN.pdf

Other Resources:

- Webinar: Re-thinking Risk: Are children too safe for their own good? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lf4n3wioRYQ

- https://brussonilab.ca/resources/

- http://childnature.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/B.-EN-Active-Outdoor-Play-Position-Statement-FINAL-DESIGN.pdf

- http://theconversation.com/why-kids-need-risk-fear-and-excitement-in-play-81450

- http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/outdoor-play/according-experts/outdoor-risky-play

- https://outsideplay.ca/

- http://www.internationalschoolgrounds.org/risk

- https://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/features/risky-play-for-children-why-we-should-let-kids-go-outside-and-then-get-out

- http://www.internationalschoolgrounds.org/risk

- https://activeforlife.com/six-types-of-risky-play/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/freedom-learn/201404/risky-play-why-children-love-it-and-need-it

- http://www.playsafeinitiative.ca/risky-play.html